Why the animist Ravenflag might be relevant again

• In Danish: Hvorfor ravneflaget er aktuelt igen på en ny måde

A world perspective that is presumably more geographically and historically widespread than any other is sweeping through the world again like a whispering wind with an overlooked momentum. It’s a wind that brings the voices of nature to life in countless new stories in books, movies and television series based on close relations of friendship and even kinship between man and nature.

This world perspective is usually characterized as animism and strikes many people as very, very strange. But the fact that it’s spreading is interesting for a number of reasons.

One of them being that we live in an age where the biodiversity and climate crisis is accelerating with catastrophical consequences. This might motivate us to rethink the very foundations of the rather hostile relations to nature that we as humans are mostly engaged in today.

And this might also explain why a flag that stems from the Viking Age has been relaunched as a contemporary symbol of the much needed connectedness between humans and nature: The Raven Flag.

1. The Climate Crisis calls for new relations between humans and nature

Homo Sapiens is merely one of roughly 10 million species on Earth. We are all historically connected in various ways, and basically we all consist of the same biological building blocks.

We are leaves on a tree and the roots of that tree are wondrously tangled ramifications of evolution that stretch back to the emergence of life in the oceans. The Blue Planet became The Living Planet. But maybe The Living Planet is also The Lonely Planet?

Either way we don’t know of any other living planet than our own. Obviously, the notion that life is absent everywhere else in the universe seems quite improbable, but in this particular solar system there is only life on one planet. Besides, the lifeless distances of the universe are literally so astronomical that we will never be travelling to another solar system on any other spaceship than that of our imagination. I guess.

However, millions of different species and maybe sextillions of individual animals, plants, and fungi of an astounding variety and beauty are concentrated right here on this very globe.

The diversity of life on Earth seems to be a unique and invaluable exception or at the very least a cosmic rarity, that we really ought to cherish and protect – and be a little more Earthbound. And yet we have never eradicated more species or impoverished nature in as devastating and often irreparable ways than today, where the activities of humans have culminated in two global catastrophes: The biodiversity crisis and the climate crisis.

We have become alienated from nature and the other species with whom we share the planet – but it wasn’t always like that.

The experience of nature as a home, that houses other species than Homo Sapiens as well as other persons than humans, is not only widespread from the Stone Age to the Iron Age, but also historically and presently among countless of indigenous peoples and in a number of religions.

Close ties are established to various species and specific natural phenomena through storytelling, visual arts, music, rituals, and customary practices, which for cultural or personal reasons seem to be of particular importance. Various animals, trees, rivers, mountains, and celestial bodies, for example, are incorporated in spiritual understandings and expressed as friendships and kinships and thereby transgress dividing biological lines.

We often characterize world perspectives of this kind as animism, although this doesn’t signify any -ism in the sense of a doctrinal system associated with some sort of articulated philosophy, ideology or religion. Fundamentally it’s a perspective deeply embedded in a widespread way of connecting respectfully to other forces and persons in nature.

In a marginal way it’s comparable to how a modern family relates to their pets, with whom children as well as adults often engage in personal relations, generally embracing them with great affection. Often by giving them names, maybe even dressing them up, celebrating their birthdays and essentially by including them as family members. It’s a behavior within the same broad spectrum as classic animist traditions, although in most contemporary views to a less controversial degree than in the kind of animist relations, where some or even all species and other natural phenomena could be regarded as actual persons (or as connected to spiritual persons).

Few people probably reflect on this while walking the dog, and for most of us an anthropocentric world perspective is alfa and omega, whereas an animist world perspective is just extremely strange. But considering the fact that animism presumably is the most common world perspective, historically as well as geographically, it’s actually not particular odd or even exotic.

We find animism embedded in major cultures, that make up most of the ancient cultural roots to the socalled Western World – Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome. But also in Northern Europe up until the end of the Iron Age, the last centuries of which are known as the Viking Age.

When people establish respectful relations of friendship and kinship to other species and natural phenomena they are less likely to be motivated by sheer greed to exploit these friends and relatives in nature. This doesn’t mean that animist relations constitute insurmountable barriers against any exploitation, or that they are devoid of conflicts of interest, but they do originate in perspectives on nature and culture, that in a number of ways contrast the destructive contemporary anthropocentric Zeitgeist. This contrast is highlighted by the unambiguous scientific realization that the evolving climate and biodiversity catastrophes are man-made.

The meticulous analyses of global data by countless scientists point to the necessity of radical societal changes in order to end the accelerating overconsumption, which ultimately is the driving force behind both global crises – and is why they are actually just two aspects of the same crisis. This might at least motivate us to take a deeper look at the cross-cultural perspectives of our animist heritage, that are anchored in a deep sense of connectedness to nature as opposed to limitless exploitation.

These ideas are already on the rise and are exemplified in the increase of collaborative projects between indigenous peoples and authorities and NGO’s with the explicit purpose to enhance biodiversity and the ‘rewilding’ of a wide variety of natural environments – while simultaneously strengthening and reconnecting with their own animist heritage. The American Bison, for example, is returned as a keystone species in some areas of the grasslands of the Great Plains in cooperation with native Americans in order to improve biodiversity and thereby create a cascade of beneficial effects that ripple out to the entire ecosystem. This is quite simply achieved as a consequence of its eating patterns, trampling, and wallowing, which benefits a lot of other species. But for many native Americans it’s also the return of Brother Bison in a profound spiritual sense.

Animism has also influenced laws and constitutions in order to protect ecosystems and species in more efficient ways by connecting to local and regional animist perspectives. Nature has been recognized as subject of rights in the constitution of Ecuador, effectively stating that Pachamama (‘Mother Nature’) is a legal person (a nature goddess revered by indigenous peoples of the Andes). In other countries rivers have been recognized as legal persons.

It’s not an uncommon understanding in contemporary Anthropology that a sharp distinction between ’person’ and ’non-person’ isn’t ontologically absolute but rather culturally determined, and animist perspectives that transgress this distinction are historically very common. We don’t even need to dive deep into history to find animism fully displayed in Western traditions and folklore.

Voluminous works about Danish folklore based on accounts from thousands of people in the 19th century describe how the rural population at that time still regarded their world as a place full of non-human persons with whom many also engaged in ritual relations. We see the same picture in other Western countries where neither the pressure from institutionalized religion nor rationalism from the Age of Enlightenment were successful in their efforts to suppress a widespread animism among the common people.

Folklore also inspired a rich fairytale tradition, in which the relations between humans and other-than-human persons is a pivotal theme, and in the 20th and 21st centuries not only comic books, cartoons and computer games have picked up the baton. Also, a number of successful novels, television and movie productions are obviously influenced by the spirit of animism, for instance global bestsellers like J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia and Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials. The same goes for James Cameron’s blockbuster Avatar, Guillermo del Toro’s Oscar-winning movie The Shape of Water and the television series American Gods, based on the novel by Neil Gaiman. And those are just the tip of the iceberg.

Animism is like a whispering wind sweeping through the world with an overlooked momentum, although hardly ever mentioned. A wind that brings the voices of nature to life in new stories but originates from perspectives that are rarely preoccupied with sharp distinctions between culture and nature or between a natural and a supernatural world. Perspectives that don’t plow through the world and leave behind the same dualistic abyss between subjects and objects, that we are so accustomed to in the anthropocentric worldviews that single out and separate humans from the rest of the world. Animist worlds are continuous like an ocean, not separate buckets of water.

This is why historical and prehistorical art, myths, and folklore are full of figures that are half humans and half animals. We know of shamans dressed in antlers and furs from rock art as well as burials, and in Scandinavia we know of similar metamorphoses from the Gundestrup Cauldron, the Golden Horns of Gallehus and numerous mask helmets. All over the world different cultures depict lion-persons and seal-persons, tree-persons and river-persons, bear-persons and raven-persons. And so forth.

When we strengthen the connectedness between humans and nature through new depictions and stories, we are also retelling animist relations and opposing the anthropocentric dissociation that has led to the indifference and greed at the core of the destruction of nature.

2. A Viking Renaissance in popular culture and spirituality

Everybody has a family tree. Not just a genealogical list of ancestral names leading back to our grandparents’ grandparents but also a cultural-historical family tree that could provide us with a deeper understanding of our culture(s) and of who we have become.

A kind of world tree with cultural-historical roots stretching back to the Iron Age, the Bronze Age, and even the Stone Age, where mythical time spoons historical time and begets the strangest of children, tell the fairest of tales and conceive the earliest of cultures. Not in the sense of homogenous cultures confined by sharp and static edges but rather characterized by some sort of societal osmosis in a dynamic and never-ending process of invention and reinvention.

Cultures are everchanging and no two humans are alike; each of us are influenced and inspired to various degrees by numerous trails of history, that aren’t confined to our homeland or to the society in which we grew up. We travel more than ever, knowledge is shared across the globe by the click of a mouse, and some of us might be less foreign to remote places and traditions than the one or the ones we are born into.

A North American of the 21st century could feel more ’at home’ in the Classical Age than in the Age of Enlightenment, feel more ’Scandinavian’ than ’North American’ in his or her cultural affiliation and be more inspired by South American than West European literature. An Indian could feel more ’at home’ in shamanism than Hinduism, feel more attached to a historical Sami world perspective than a contemporary ‘Indian ideology’ and feel more enthusiastic about African than Asian art. However, at the same time they could both feel connected to their surroundings and neighborhoods in several different ways.

If the concept of ’tribe’ makes any sense in my part of the world today, my tribe could consist of people from different parts of the world, of whom most of us might never meet or even know the existence of each other. This calls for respect of those remote branches of cultural history we let ourselves get inspired by, especially when they have roots, which other people still are born into and regard with great esteem and affection.

Respectful cultural inspiration (in the meaning of spiritual enrichment or intellectual enlightenment) is nothing but constructive education and attentive recognition, not to be confused by cultural appropriation (in the meaning of monetary enrichment, deliberately ridicule or downright political abuse), which is destructive theft and contempt.

Today, the Viking Age seems to be undergoing a kind of renaissance, which a lot of people embrace with different levels of historical knowledge and understanding – and not just in Scandinavia, where it historically ’belongs’ or at least originated.

Unfortunately, this extensive appeal is also reflected in counterfactual historical ideas with racist and nationalist intentions, even if both concepts are completely alien to the Viking Age.

More influential, however, is the globalization of the Viking Age in popular culture, where everything with the slightest association to Vikings has exploded on social media as well as in games and movies, that span from imaginative retellings of legendary saga figures to the Marvel universe of superheroes – often as disconnected from the law of gravity as it is from cultural history.

Furthermore, the mythology and aesthetics of the Viking Age is a popular pool of inspiration within tattoo art, jewelry and ambitious music based on in-depth historical studies, not to mention spiritual motivation in institutionalized settings as well as more diversified animist trends.

One is almost inclined to say that the Vikings has yet again set sail for distant shores in a different but greater conquest – this time armed with myths, music, and merchandise.

But the most romanticized tendencies of the contemporary Viking turmoil are clouding the fact, that the Viking Age probably isn’t the most adequate cultural term for the last centuries of the Iron Age in Scandinavia. After all, ’Viking’ was a rare occupation. The word víkingr basically means something like pirate or sea warrior, whereas the word víking signifies an activity that might include raiding as well as trading. It was something that some, but far from all Scandinavians did from time to time.

On the other hand, Viking and the Viking Age are obviously established terms in research as well as popular culture, and despite widespread inaccuracies and ahistorical misuse on the Internet and in movies and tv-shows there is no doubt that the Viking phenomenon affected cultural history in significant ways, although the Viking label only covers a minor part of the content of that era.

And, of course, there is nothing wrong with being inspired selectively and feeling attached to specific cultural historical roots as a personal choice. But obviously some knowledge of the context of the entire root system is both beneficial and of relevance to any such choice. For instance, central parts of the Viking legacy, that are seeping through literary sources and interpretations of archeological findings point at underlying spiritual relations to nature. Here we find that humans are physically as well as spiritually anchored in nature – as beautifully expressed in Vǫluspá, the prophecy of the Völva, according to which the first humans, Ask and Embla, are created from two trees.

Scandinavia remains pagan longer than most of Europe, but spiritual relations to nature are formally overthrown by church dogma around the end of the 10th century. In other words, the sacralization of nature that has been a ritualized part of life since the Stone Age is suppressed as evil paganism and dangerous witchcraft, whereby a universal core and continuity of our cultural heritage seems amputated. The animist world perspective that is characterized by a continuous cosmology of kinship between humans, nature and spirits in an interconnected universe is replaced by the discontinuous realms of God and humans as well as the disconnected kinships of humans and nature.

Yet, these formally imposed fractures aren’t as deep-rooted as one might think. As previously mentioned, extensive folklore studies show that common people have just been less outspoken, and that places and spirits of nature are often revered as late as the end of the 19th century.

But the Viking Age is the latest era in Scandinavian history where this sense of connectedness and kinship with nature is still unfolded in society as a whole and thereby linked to a much older heritage. Nevertheless, the most common symbols that are associated with the Viking Age today are probably the Viking ship, the Runes, and the hammer of Thor, and they don’t really express the significance and continuity of the relatedness to nature.

Therefore, it’s in nature itself that we find a more proper symbol of kinship between humans and nature, that doesn’t just characterize the Viking Age but also its prehistoric roots: The Raven.

Ravens are a common motif in Iron Age jewelry, and in some cases brooches, so called fibulae, are designed to express human and animal nature combined: A Raven incorporating an anthropomorphic mask. As a scavenger the Raven could be seen as a mediator between the realms of the living and the dead, and according to several literary sources a Raven banner likewise served as a war standard in the Viking Age.

Even so, we hardly need to stimulate the conquest of land and wealth in our day and time where nature is being ravished by narrowminded overconsumption resulting in the climate and biodiversity crisis. Rather, we should reconquest a respectful but abandoned connectedness between humans and nature.

A pair of Ravens that are particularly well known by most people, Huginn and Muninn, not only function as world-bridging messengers but also embody human mental capabilities that can be translated to mind and memory. They transgress the divide between bird and man and in a broader sense express the close relations between culture and nature that are part of the core and continuity of a heritage embedded in the Viking Age – which our anthropocentric present has yet to rediscover.

3. The next kinship between humans and nature

Homo Sapiens is (also) an animal. But it’s hardly something we reflect a lot upon.

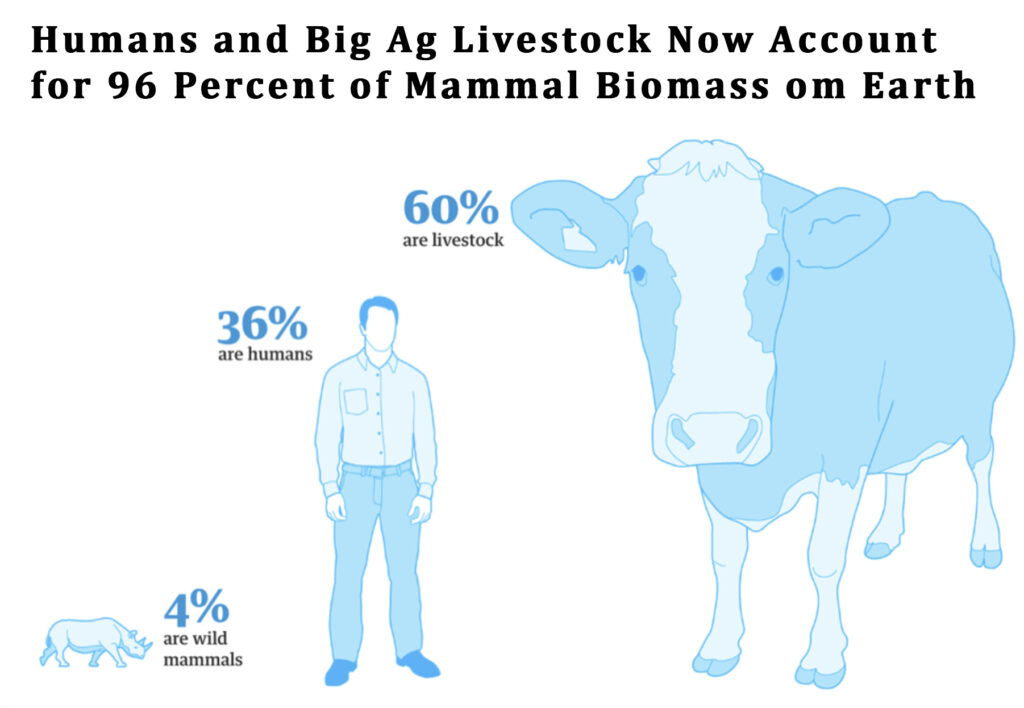

Rather, it’s something we are inclined to forget, especially considering the hardships that billions of other animals must endure because of us. One need just to mention the harsh conditions in the battery cages of factory farming that almost make herrings in a barrel look like a luxury cruise. But in face of the brutality to which we submit industrially farmed animals as well as nature as a whole we prefer to avoid any recognition of the fact that we too are animals.

Of course, humans have always been eating meat, but we have not always killed animals with the same cynicism that we have grown accustomed to in our anthropocentric era. Now we stick to the spoken or unspoken conviction that we are disconnected from and utterly incompatible with the animal kingdom.

Perhaps it would have been harder to instrumentalize this cynicism if we had been a lot more aware of our common origin and the connectedness of life?

Naturally, it’s easier for us to overlook the similarities and only notice the differences between humans and all other animal species, when most of us have virtually no real knowledge of the animals before they are reduced to a pound of clay-like minced meat wrapped in plastic or stuffed in sausage casings of animal intestines.

Or – if not destined to be served on a plate – as pets or in circus and sports where animals are expected to fulfill the increasing needs of man’s amusement but obviously unable to exercise their natural behavior in the wild.

However, be it far from my intention to claim that pets and other ‘amusement animals’ aren’t generally cared for and treated well by most people as opposed to the vast majority of industrially farmed animals.

But our lack of empathy with billions of animals, be they confined to narrow cages their entire lives or be they wild animals deprived of their natural habitats, are signs of our forgotten ability to understand the kinship to nature by which we have felt connected in most of our cultural history.

Humans are (also) animals, even if we have developed skills to dominate most of the planet with such devasting imprints on global ecosystems, that our era is named Anthropocene – the Age of Humans.

The connectedness between humans and nature has deep biological as well as cultural roots, which we have discarded with far reaching consequences for hundreds of millions of people who might lose their homes and livelihoods and face an inconsolable fate as climate refugees in decades to come.

And with devastating consequences to countless of our fellow species on Earth, who are threatened with downright extinction due to a vast and often irreversible loss of habitats.

Animist perspectives might be an antidote against our culturally determined belief that there are only subjects ‘inside’ humans, and that these subjects perceive the ‘outer’ world accurately and objectively as a bunch of mindless and soulless objects and in the process – not surprisingly – crowning our ego as an emperor whose needs everything else revolves around and is subjugated.

In other words, animist perspectives might help us to bridge the rather self-indulgent gap in our heads that keep echoing of an anthropocentric wiring of the human mind as an isolated ‘me-sphere’ categorically detached from the rest of the world. Such sharp distinctions are just how we often frame ourselves in the world today (whether we are conscious of it or not), but it’s not the only way and it’s not a more truthful way than we find in every other perspective.

Animist perspectives are relevant to reflect upon in a global nature crisis but also in a broader sense in contrast to the anthropocentric mantras “me, me, me” and “more, more, more”, where spiraling greed and cynicism not only replace nature’s diverse beauty with the endless monotony of plantations and concrete but also deepens inequality among nations as well as among people to levels of an astounding absurdity.

In addition, knowledge of these perspectives provides us with a deeper understanding of our own cultural-historical heritage in the West which is also entangled in a continuity of animism and closer kinship ties to nature – an imminent part of the animist perspective. A world with smaller egos but with more persons and capacious identities.

Practically 99 percent of the entire era of Homo Sapiens has taken place in surroundings that could be characterized as sheer wilderness. In that respect it isn’t odd, that we still feel some sort of uplifting mental sensation even just by observing nature. It’s difficult to express in words how and why nature is this kind of solace to the soul, but perhaps we are instinctively reminded of the fact that our body and mind has evolved in – and is evolutionary adapted to – the experience of nature?

Once upon a time we had room for the wilderness outside as well as inside ourselves, so to speak, and culture and nature weren’t contradictions but fluently interconnected. Today we have abandoned and repressed, crumbled, and thrown away nature in most parts of the world. So, what to do when you want to recover something that’s been misplaced? You return to where you last remember seeing it before you lost it.

And in this part of the world, where I live, it’s not so much a place as it is an era – the Viking Age. As late as the end of the Iron Age relations to nature could still be a vital part of the spiritual and cultural life, even of the identity of man. And in the Viking Age one specific bird might symbolize the relation between humans and nature: the Raven.

Likewise, the Raven is an important person in a number of indigenous cultures and traditions from the Northern Hemisphere, often as a socalled trickster. Not only does the trickster exceed the borders between worlds but also between humans and animals, between solemn seriousness and down to earth comedy, between egotism and altruism. Other tricksters appearing in different animal guises have fulfilled similar roles in countless cultures – bear, hare, crow, fox, spider, and many others.

We are connected with nature, but we have neglected and ravished this connectedness in an era that confronts rather than respects nature. Animosity instead of kinship. That’s why it’s important to recover and retell this connectedness again. In new and old ways and in new and old shapes. In individual and common ways and in individual and common shapes.

This is why also I raise the Raven Flag. But it needn’t just be this flag. Any Raven flag – or an entirely different species for that matter – can express and reinvent this connectedness to nature in whatever way or shape it feels individually relevant to reestablish. For those of us who wish to symbolize and exert a dissociation from escalating egotism and anthropocentrism.

Rune Engelbreth Larsen, November 2021

A very special thanks to Rithma Kreie Engelbreth Larsen and Rune Hjarnø Rasmussen

NOTE: This essay is also available in Danish: Hvorfor ravneflaget er relevant igen på en ny måde. Also check out the poem The Raven flag and the three Youtube-videos based on this essay.